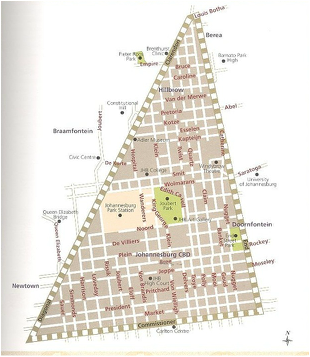

Hillbrow is a one square kilometre area that formed part of the original Johannesburg. Johannesburg’s history stretches back to a Sunday in March, 1886, when Australian, George Harrison, stumbled upon surface outcrops of gold-rich conglomerate on a farm-land near the centre of Johannesburg. Gold changed the face of Johannesburg. Before 1886, it had been a struggling Boer republic, but 10 years later, it was the richest gold mining area in the world. As news of the gold find spread throughout South Africa and the rest of the world, men made their way to Johannesburg. President Paul Kruger appointed a commission to survey a site for a township to service the new goldfields. A triangular two-and-a-half square kilometre piece of “uitvalgrond” (ground left over) from the three Boer farms – Braamfontein, Turfontein and Doornfontein was identified and duly mapped out. The booming mining town required cheap, unskilled labour and so within just a few years, many thousands of men were leaving their homes from all over the world to join the unskilled migrant workers who flocked to Johannesburg for the low wages on offer. From its early beginnings, white “Randlords” (a term used at the time to describe the entrepreneurs who controlled the diamond and gold industries in South Africa in its pioneer phase) lived in opulence while the predominantly black Mineworkers were subjected to humiliating, degrading and exploitative conditions. Many historians argue that the system of racial discrimination is rooted in the migrant labour system. The popular song by Jazz musician Hugh Masekela, entitled Stimela (the coal train) describes quite well these tumultuous times and what they must have meant for the men who flooded to Johannesburg: "There is a train that comes from Namibia and Malawi There is a train that comes from Zambia and Zimbabwe, There is a train that comes from Angola and Mozambique, From Lesotho, from Botswana, from Swaziland, From all the hinterland of Southern and Central Africa. This train carries young and old, African men Who are conscripted to come and work on contract In the golden mineral mines of Johannesburg And its surrounding metropolis, sixteen hours or more a day For almost no pay. Deep, deep, deep down in the belly of the earth When they are digging and drilling that shiny mighty evasive stone, Or when they dish that mish mesh mush food into their iron plates with the iron shank. Or when they sit in their stinking, funky, filthy, Flea-ridden barracks and hostels. They think about the loved ones they may never see again Because they might have already been forcibly removed From where they last left them Or wantonly murdered in the dead of night By roving, marauding gangs of no particular origin, We are told. They think about their lands, their herds That were taken away from them With a gun, bomb, teargas and the cannon. And when they hear that Choo-Choo train They always curse, curse the coal train, The coal train that brought them to Johannesburg" Over 125 years later and they continue to come, migrant workers flock to “eGoli” (the city of gold). For many who flock to South Africa, the city centre of Johannesburg, and in particular Hillbrow, is the starting point. Many who come are fleeing economic meltdowns, poverty and conflicts which have besieged the African continent. While gold is no longer mined close to the centre of Johannesburg, its bedfellow, the South African Rand, still lures men from across the continent. Many of the remnants of the multi-tentacled legacy of the migrant labour system still linger and have left the city and its people scarred. As I dream of Shalom for my community, I am cognisant of the haunting voices from our history, reminding me that forces larger than I have for centuries been at work dehumanising, violating, destabilising, demonising, and opposing God’s vision of Shalom.

0 Comments

|

Archives

October 2020

quick links

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed